Dutch & Dutch 8c Active Loudspeakers (http://bit.ly/2JqVmsr)

When Doug Schneider asked me to review the 8c active loudspeaker from Dutch & Dutch, my first reaction was: “Dutch and what?”

I looked up the 8c on Dutch & Dutch’s website, and the description was intriguing: a speaker with built-in preamp and power amp, subwoofer, DAC, digital volume control, IP control, and advanced digital signal processing, all in a package that fits on a pair of minimonitor stands and costs $12,500 USD per pair. The 8c’s home page states: “Accurate. Adaptive. All-in-one.” My response to Doug was enthusiastic: “Yes, please — I’d love to review this product.”

Description

Dutch & Dutch was founded in 2014, but didn’t sell its first pair of speakers until late 2017. The 8c is their sole model. When I asked Martijn Mensink, a founder and lead conceptual and acoustical designer, about the names of the company and its speaker, he told me that 8 stands for the speaker’s three 8” drivers (two subwoofers and a midrange, all with aluminum cones), and c for the midrange’s cardioid radiating pattern (more on this below). As for Dutch & Dutch, the speakers were designed and are manufactured in the Netherlands by proud Netherlanders. They thought the name was catchy.

The 8c’s dimensions of 19.1”H x 10.6”W x 15”D may be on the large side for a bookshelf speaker, but when you consider all the drivers and electronics each cabinet contains, it’s astonishing that D&D could squeeze it all in. Each speaker weighs 57 pounds — I grunted each time I picked one up. The 8c is available in four finishes: White/Natural, Black/Natural, Black/Brown, and Black/Black. The first word in each pairing is the color of the plastic front baffle; the second describes the finish of the 19mm-thick cabinet walls of solid oak, which enclose a subcabinet of 18mm-thick birch plywood. My review samples, in Black/Natural, looked great; the natural oak finish of the top and side panels was top notch.

The look of the 8c took some getting used to. Its general appearance exudes professional audio (e.g., recording studios, sound reinforcement at live events, etc.), but with a few touches of high-end home audio, such as the quality of the wood finish and the baffle’s attractive curves. Indeed, D&D’s website makes clear that the company attempts to walk the line between pro and upscale consumer audio, to appeal to both segments of the market with a single product.

The 8c’s connections and switches are all in a row along the rear bottom of the cabinet. From left to right are: the single input, labeled In (balanced, XLR); a balanced output, labeled Thru (XLR); a balanced subwoofer output, labeled Sub (XLR); a Network input (Ethernet); an input selector, labeled Set, with LED indicators for Hi, Lo, L, R; a main power switch; and the inlet for the power cord (110-230V/50-60Hz). Set selects among four types of balanced inputs: analog high level (+4dBu, typical for pro-audio equipment), analog low level (-10dBV, typical for line-level consumer gear), and AES3 Left and Right, for the two channels of a stereo digital AES/EBU signal. Cycling through the Set settings gives you a fifth option, AES3 Mono (both L and R LEDs illuminated), in which both channels of a stereo AES3 digital input are summed to mono.

The Network Ethernet input is self-explanatory (the 8c has no Wi-Fi adapter), and is required only to control the 8c’s settings, which is done through a web-based app accessed through the D&D website. Once these settings are made, the 8c’s will work fine without being connected to your home network. The balanced Sub output can be customized through the app, which can also be used to apply various equalization options: high-/low-pass filters, peak filters, delays, phase inversion, etc. The balanced Thru output accommodates users who want to feed the 8c a digital signal via a balanced AES/EBU 110-ohm cable. You connect the digital source to the left (or right) speaker input, select L with the Set button, then connect the Thru output from the left speaker to the single input of the right speaker, select R with Set on the right speaker, then finally insert the XLR termination connector (supplied by D&D) in the Thru output of the right speaker. Since all functions, including the crossover, are implemented in the digital domain, the 8c immediately converts all analog signals to digital with its built-in A/D converter.

The curious reader may be wondering: “This active speaker really has only one input connector?” That’s right — conspicuously missing from the 8c’s rear panel are all other inputs, especially digital ones such as USB, optical, and coaxial. But audiophiles often demand lots of input/output choices. When I asked Martijn Mensink about this, he told me that D&D is working on an external companion preamplifier for the 8c that will have all manner of analog and digital inputs. They’re also working on Roon integration for direct streaming to the 8c. Stay tuned.

For technical descriptions of the drive-units, I relied mostly on Mensink’s enthusiastic explanations. He told me that each driver is truly pistonic within its passband, meaning that there are no breakup modes within the bandwidth of frequencies assigned to each to reproduce. The bass is handled by two high-excursion subwoofers mounted on the rear of the cabinet’s sealed enclosure and driven by a 500W class-D amplifier. These woofers are designed to work with the room’s front wall, which, ideally, would be between 8” and 32”from the rear panel. Basic bass tuning is accomplished internally with DSP using the distances of the speakers from the side and front walls, entered by the user in the app. Because the wall is geometrically close to the speaker in terms of wavelength, and because bass frequencies radiate omnidirectionally, the wall functions as a sounding board for the bass, the outputs of subwoofers and wall combining to become one in a hemispherical radiation pattern directed at the listener. According to Mensink, this use of the front wall provides two important benefits: a 6dB boost in sound pressure compared to a freestanding speaker, and improved dynamics and punch (i.e., tighter bass) due to the resulting phase-coherent low-frequency wavefront.

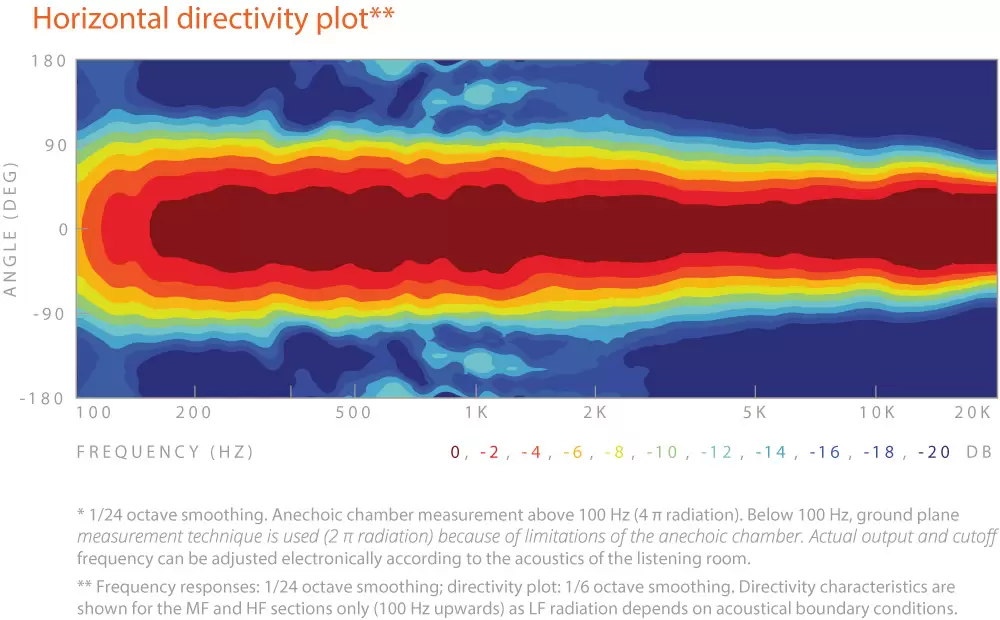

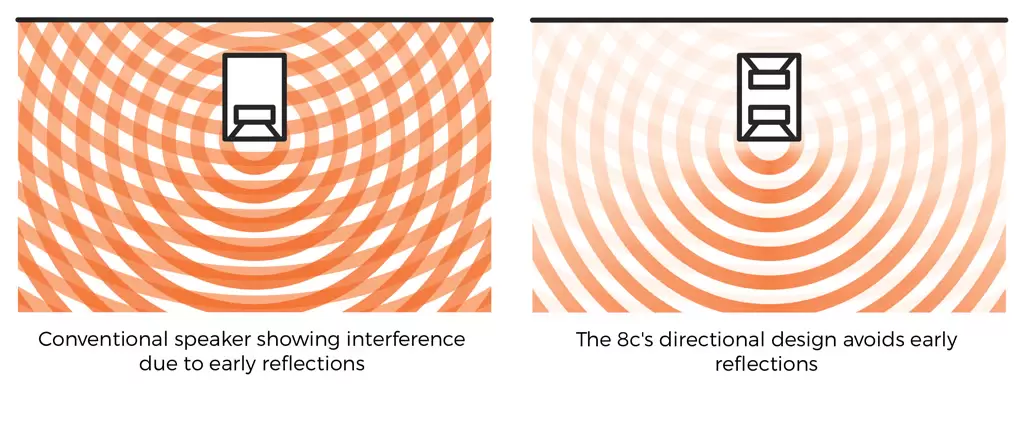

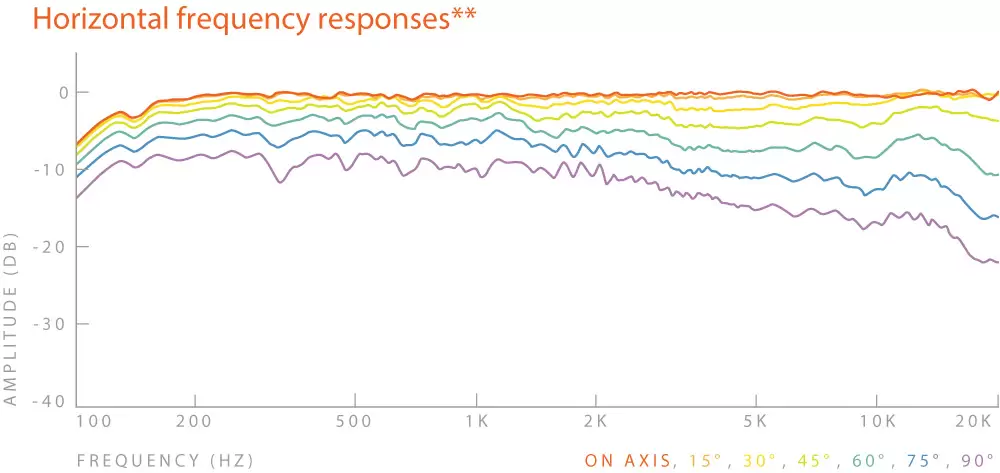

Above 100Hz, the frequency at which the subwoofers hand off to the midrange driver via a crossover with fourth-order Linkwitz-Riley slopes, the 8c radiates as a cardioid in a manner analogous to how a cardioid microphone works and unlike how most speakers work. In conventional speakers, the soundwaves radiated from the back of the driver diaphragm are a problem that must be dealt with. The designer may try to dissipate these unwanted frequencies as delayed resonances through the enclosure panels. To achieve this, they may increase the panels’ mass, damping, and/or stiffness, and use damping material inside the enclosure to convert these resonances into heat. In the 8c, the out-of-phase sound from the rear of the midrange diaphragm is filtered and delayed within the acoustic cardioid subenclosure before exiting the cabinet through a long vertical slot on each side panel. The sound radiated from the front of the driver and the out-of-phase sound emitted through the slots meet each other toward the rear of the enclosure, where they cancel each other out. Unlike the subwoofers’ output, which is reinforced by the wall behind the speaker, the midrange frequencies that would otherwise be headed rearward are mostly canceled out — acoustically speaking, the wall isn’t there at all (cardioid pattern), which effectively eliminates unwanted midrange front-wall reflections. According to Mensink, the 8c’s radiation patterns — hemispherical for the subwoofers, cardioid for the midrange — are very close in directivity and blend seamlessly, enabling the 8c to work well in most rooms.

At 1250Hz, the aluminum midrange driver is crossed over to the 1” aluminum-magnesium dome tweeter, again with fourth-order Linkwitz-Riley slopes. This frequency would usually be considered quite low for a tweeter — most manufacturers cross a tweeter over at 2kHz or higher. This frequency works well in the 8c, Mensink told me, because D&D has chosen a very robust tweeter and mounted it in a waveguide, or “acoustic amplifier,” that serves two functions. First, it increases the tweeter’s efficiency, enabling it to play louder with the same input signal. As a result of the lower power consumption, the crossover frequency can be lowered without fear of overloading the tweeter. Second, the waveguide controls the tweeter’s directivity; its on- and off-axis responses closely match those of the midrange driver, for a better blend of their outputs. Both waveguide and front baffle are smooth and rounded on all edges to minimize diffraction, for clean wave launches from the tweeter and midrange driver, each powered by its own 250W class-D amplifier.

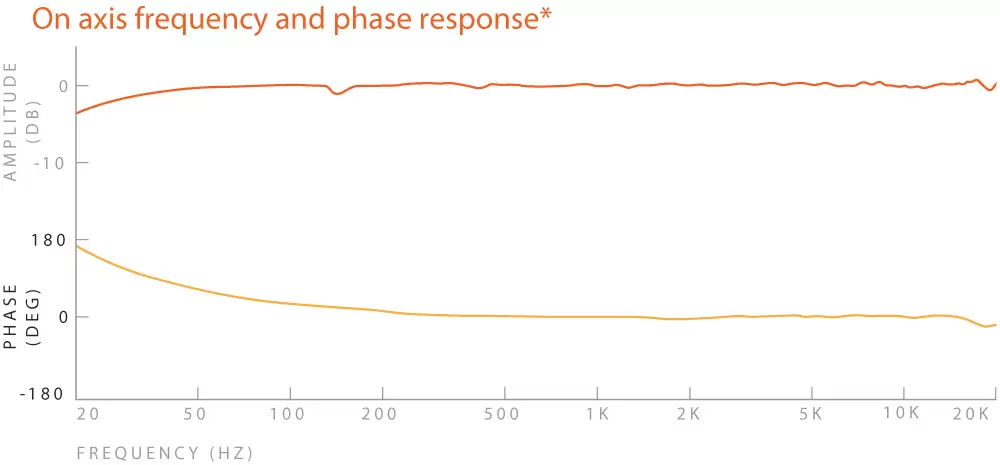

D&D publishes few specifications for the 8c: a frequency response of 30Hz-20kHz, ±1dB; a maximum output, measured at 1m, of 106dB from 35Hz up; and a signal/noise ratio of >118dB. Thermal and DC-clipping protection mechanisms are built in.

Setup

Dutch & Dutch take great care in protecting their first creation, double-boxing each speaker, but unpacking the 8c’s was easy. Included with each speaker are a 15’-long Ethernet network cable, a 6’ power cord, a pair of white cotton gloves (nice touch!), and one XLR termination connector per speaker pair, along with instructions on how to connect a digital source to the 8c. When I set the 8c’s atop the 25”-high Bowers & Wilkins stands that I use for my B&W 705 S2 speakers, they looked pretty big, and at first glance seemed to be sitting too high. But when I sat down to listen, I realized that my ears were on a level halfway between the top of the midrange driver and the tweeter — perfect.

The speakers formed a 9’ equilateral triangle with my listening chair, toed in 18°. I connected the balanced outputs of my McIntosh Laboratory C47 preamplifier to each 8c’s balanced XLR input and powered up the speakers. The 8c takes about 35 seconds to boot up, after which an internal relay gently clicks and a white LED at each speaker’s bottom front lights up. I left my miniDSP DDRC-22 processor in the signal chain between my Bluesound Node streamer and the C47’s DAC, but made sure to disable the Dirac Live filter so that no room correction would be applied. So configured, all the DDRC-22 does is upsample incoming PCM data to 24-bit/96kHz.

Audio purists might raise an eyebrow, as did I, at the fact that the 8c immediately converts all analog signals to digital to then subject them to DSP. When I mentioned this to Martijn Mensink, he conceded that while theoretically it would be advantageous to feed the 8c a digital signal whenever possible, D&D’s listening tests have convinced him that the 8c’s A/D conversion is all but transparent. He described the differences in sound between feeding the 8c’s analog and digital input signals as being subtle in sighted tests, and extremely difficult to almost impossible to hear in blind tests. I would like to have fed the 8c a digital signal, but I lacked the required AES/EBU 110-ohm XLR interconnect.

The next step was to configure the room boundary positions in the 8c app. Because I have only one Ethernet network connection in the room, and my one and only Ethernet switch was already dedicated to my home network, I had to configure each speaker individually. Note: If you want to group and control (e.g., the volume) two 8c’s together via the app, each 8c requires its own wired network connection. In the app, distances from the speakers to room boundaries can be entered in values ranging from 20 to 80cm, in 10cm increments; the Free setting is for distances in excess of 80cm. I reached for my measuring tape and measured 85cm from the center of the rear driver to the sidewall, and 52cm from the center of the rear driver to the front wall. So I selected, respectively, 80 and 50cm for each 8c.

My first impression of the 8c’s was “Why are they so quiet?” I had to turn the gain on my preamp way, way up. Then I realized that the default volume setting in the 8c app is -30dB, and promptly changed it to 0dB. My second reaction was one of enthusiasm for the overall sound, but the bass was so boomy that I felt compelled to use the app’s Bass Control function and dial in a -6dB cut. This helped, but the boom persisted. When I spoke to Mensink about this, he suggested I move the speakers closer to the front wall. As counterintuitive as that was, I nudged the speakers back about 8cm — voilà, the boom was gone. I returned the 8c app’s Bass Control to its flat (0dB) setting and the bass seemed just about perfect.

Was this the 8c’s innovative, DSP-controlled, room-coupling bass-tuning technology at work, or was it just my dumb luck in moving a room bass mode away from the listening position? I’m not sure, but I’m assuming a combination of both.

The final adjustment involved choosing between a front-wall room boundary setting of 40 or 50cm, as the speakers were now 46cm from the wall behind them. I settled on 40cm, which seemed to provide slightly deemphasized but more accurate bass. Those concerned about not having my good luck in achieving satisfying and accurate bass in their rooms shouldn’t worry — in addition to its configurable subwoofer output, the 8c control app offers a full parametric equalizer with up to 24 user-adjustable filters. Users experienced in setting EQ could use this, together with in-room measurements taken with something like Room EQ Wizard, to achieve bass response as perfect as their rooms permit.

Sound

Sound

Because the Dutch & Dutch 8c is an active speaker that includes amplifiers and other electronics, it produces its own noise — not much, but the review samples weren’t dead quiet. With an ear to a tweeter I could easily hear some hiss, but no hum when I moved that ear down to the midrange and woofers. This was more noise than one of my B&W 705 S2 speakers produces when connected to my very quiet McIntosh Laboratory MC302 power amp. In fact, the MC302 is so quiet that I can easily hear the noise contributed by my McIntosh C47 preamp when I turn it on (again, with an ear to a tweeter). Not so with the 8c — whether the C47 was on or off didn’t change the amount of noise produced by the 8c’s tweeter. Clearly, the 8c’s own noise was the main contributor to the overall level of noise I heard through these speakers — but it made no difference in the listening experience. Sitting in my listening chair in my very quiet basement listening room (no windows, double wall insulated, no HVAC in or out), I could hear no noise at all from the 8c’s.

The first cut I listened to was “New Orleans Is Sinking,” from the Tragically Hip’s Yer Favourites (16-bit/44.1kHz FLAC, Passport Audio/Universal Music Canada). Since lead singer Gordon Downie’s death in October 2017, I always get a little emotional when listening to him. I’m sure that any Canadian reading this can relate — the band is an inextricable part of Canada’s cultural fabric. The D&Ds’ reproduction of this song didn’t temper my response — on the contrary, their realism and transparency made the entire experience more moving.

The first thing I noticed was the bass . . . oh, the bass: taut, firm, warm, deep — and, as I stared at these relatively small cabinets, difficult to comprehend. Measurements of the sound-pressure level in my room, taken with my calibrated UMIK-1 microphone, showed that even at 20Hz, the SPL was about 3dB above the response at 1kHz. We’re talking full-range sound from what is technically a bookshelf speaker. That’s not just exceptional — it’s incredible.

The midrange was detailed, smooth, and neutral, without audible cabinet colorations. The essence of Downie’s voice came through the 8c’s astonishingly well, placing him dead center in the room, in front of me. The electric guitars were reproduced with grunt and feel, appropriately positioned and sized on the soundstage. My overall impressions of the D&Ds’ sound were that they were smooth and neutral, accentuating or muting no part of the audioband over other parts, and clean even when played very loud. These babies could rock so well that I couldn’t find an SPL at which they began to sound strained or edgy — all I heard was more and more music, the only limiting factor being the preservation of my hearing.

Next up was “I Can’t Make You Love Me,” from Bonnie Raitt’s Luck of the Draw (16/44.1 FLAC, Capitol). Here the 8c’s pulled off the illusion of “disappearing” as the sources of the sound — something I always look for in speakers, and love when I find a pair that can do it. Raitt’s voice sounded beautiful, seductive, and smooth, with no sacrifice of detail or presence, the image of her voice just above the speakers and behind the plane described by their front baffles, where I believe it should be. The tight, ample bass gave me a warm, fuzzy feeling. Tony Braunagel’s subtle cymbal work was laid bare with delicacy and nice decays, imaged just to the right of and above the left speaker. Again, the urge to turn up the volume was strong — the lack of any glare or edge in the sound felt like an open invitation to do just that. I slowly inched the volume knob clockwise, further immersing myself in the sonic landscapes the 8c’s conjured.

“One Light Left in Heaven,” from Blue Rodeo’s The Things We Left Behind (16/44.1 FLAC, Warner Music Canada), is exceptionally well produced — when I listen to this track through a good system, the you-are-there realism of the voices and guitars always draws me in. Here, too, the D&D 8c’s didn’t disappoint. Jim Cuddy’s voice sounded smooth, almost real enough to touch. The acoustic guitars, one each to left and right of Cuddy, also sounded eerily real, each occupying its own distinct space on the stage. Also in this track is a woman singing a very subtle backing vocal — the kind of subtlety the casual listener might miss if not listening carefully. The 8c’s delivered this singer’s delicate nuances incredibly well, and put her slightly to the right of and behind Cuddy — the speakers didn’t unnaturally accentuate her presence, but made her impossible to miss.

The 8c’s had proven that they could rock and play really loud, but I wanted more. “Like a Stone,” from Audioslave’s Audioslave (16/44.1 FLAC, Sony Music Entertainment), is well-recorded hard rock, and the album’s mastering is well regarded — the late Chris Cornell, who wrote all the lyrics and sings lead, was a self-proclaimed audiophile. Again, the first thing that struck me was the bass: so very, very tight. Wow. It felt as if Brad Wilk’s drum kit was in the room — I could feel the low-frequency wavefront from his kick drum hit my chest. In the loud, complex chorus, I turned it way up and heard no compression, no obvious distortion, edge, or glare. Cornell’s guttural howls came through, overlaid with the lead and rhythm guitars — no detail was compromised. It was as if I could play at rock-concert levels — I pushed it just past 100dB SPL — without the crappy sound of a rock concert!

I wanted to try a simpler arrangement: “Nightswimming,” from R.E.M.’s Automatic for the People (16/44.1 FLAC, Warner Music Canada). Most of this track is just Michael Stipe’s distinctively wailing, emotive singing, accompanied by Mike Mills on piano. Eventually, there’s also a lovely arrangement for violins and violas. Here the 8c’s showed that, in addition to big and loud, they could also do simple and nuanced. The piano’s opening notes had weight and delicacy, the plunk of each keystroke distinctly decaying into oblivion. When Stipe enters, the piano remained perfectly balanced on the soundstage, off to right of and below Stipe’s tightly focused voice — but every keystroke could still be heard, spreading out to occupy the appropriate width. The 8c’s reproduced Stipe’s voice smoothly, without glossing over any of the nuances in his singing that convey such feeling. The strings were also reproduced with delicacy and realism. The soundstaging was exemplary, showing me precisely the space the strings reside, mostly to the left of and behind Stipe. Each element of the mix was presented by the 8c’s in perfect balance with the others. A lovely experience.

The 8c’s low-end prowess in my small (15’ x 12’) listening room was impressive for a speaker of any size — so impressive that I invited my wife down to hear a recording of her choice. I knew she’d go for hip-hop, and sure enough, “All Me,” from Drake’s Nothing Was the Same (16/44.1 FLAC, Cash Money), was soon playing at an entirely unhealthy volume. The electronic bass in this track includes some constantly pulsing, very-low-frequency tones intermingled with bursts of punchy bass notes. The experience was unforgettable — like being wrapped in a warm, cozy blanket while being occasionally punched very firmly in the chest. After we’d listened to half of “All Me,” my wife turned to me. “Do you have to give these back?”

Dutch & Dutch vs. McIntosh-B&W-SVS and Dirac Live

I pitted the Dutch & Dutch 8c’s against a system comprising Bowers & Wilkins 705 S2 speakers driven by a McIntosh Laboratory MC302 stereo amp via my homemade speaker cables, augmented by an SVS SB-4000 subwoofer connected with Monoprice Premier balanced interconnects (XLR) — all subjected to room correction courtesy Dirac Live. (Both systems had a front end consisting of a McIntosh C47 preamplifier and a Bluesound Node streamer.) Was it a fair fight? It is if you add up the prices: the B&Ws, SVS, McIntoshes, and Dirac Live total $11,225 to the D&Ds’ $12,500. Was it fair to throw in room correction? Yes — operated in their most basic configuration, as I did for this review, the 8c’s in fact rely on DSP correction of their bass output.

When Martijn Mensink and I discussed room equalization, he made clear his strong feeling that speakers, and especially the 8c, shouldn’t be equalized above the Schroeder frequency (around 200Hz in most rooms). While I might agree that a speaker designed to sound accurate shouldn’t be equalized above 200Hz in an acoustically treated, symmetrical room such as mine, I tend to disagree with the notion that EQ above 200Hz is never useful. In the case of my B&W 705 S2s, Dirac Live has been a game changer in not only providing accurate bass with seamless integration of my SVS sub’s output, but also taming the B&Ws’ hot tweeters and thus excessive sibilance in some recordings, all without significantly altering the B&Ws’ open, detailed midrange. As a frame of reference, my target Dirac Live frequency-response curve looks like the Harman target curve: +5dB and flat from 16 to 50Hz; a ski slope down to 300Hz, 0dB; flat from 300Hz to 3kHz; and a gentle slope down to -2dB at 16kHz.

To reasonably match the output levels for these comparisons, I played a 1kHz warble tone through both systems, and measured the results at the listening position with an SPL meter. The 8c’s played 3.5dB louder than the McIntosh-B&W-SVS combo. Taking advantage of the D&Ds’ volume controls, I decreased the gain for each speaker from 0 to -3.5dB, and bingo — no need to fiddle with the preamp’s volume control between takes.

My first impression was that the two systems sounded more alike than I’d anticipated. That the 8c’s sounded similar to a system room-corrected to sound flat through the midrange was a testament to D&D’s goal of accuracy. Both systems delivered realism and transparency in spades, and both pairs of speakers could “disappear,” with no hint of cabinet colorations to remind me that the sound was being produced by pairs of boxes.

There were differences. In Audioslave’s “Like a Stone,” I noticed how much more punchy the bass was as reproduced by the 8c’s. There was also more bass overall. I’m not saying that the two 8” subs in each 8c could produce more bass output than the 13.5” driver in the SVS SB-4000 — they couldn’t. If I turn up the sub’s gain to unnatural levels, the SB-4000 makes the entire house shake. (In fact, I have just such a preset on the SVS so that my wife can thoroughly enjoy her hip-hop.) What I’m saying is that the quality of the bass produced by the 8c’s — that taut, tight, punch in the chest — could not quite be achieved with my reference setup. Through the 8c’s, the opening bass-guitar notes of this song were a bit bloated compared to the McIntosh-B&W-SVS rig. Of course, I wasn’t using the D&Ds’ parametric EQ — I have no doubt that this small issue could have been EQ’d away. The takeaway: The D&Ds’ bass response was truly phenomenal; never would I have expected these little active speakers to be able to compete against a true subwoofer.

In the midrange, voices and electric guitars sounded a bit more forward through the McIntosh-B&W-SVS combo, giving an impression of more detail. The earthy, guttural quality of Chris Cornell’s voice in “Like a Stone” was better conveyed by my reference rig, and the guitar in the chorus had more bite. When I looked again at my in-room measurements of the 8c’s, this made sense — although their overall frequency response was exceptionally smooth, there was a small dip between 2 and 3kHz. The 8c’s weren’t masking detail; but at the same volume level (normalized to 1kHz), they sounded a bit more recessed — this invited, even urged me to turn up the volume to hear more into the music. Which brings us back to one of the D&Ds’ strengths: They sounded neutral, smooth, and could play LOUD. In that regard they blew the McIntosh-B&W-SVS combo out of the water — my reference gear simply doesn’t sound as clean and as free of glare at very high volumes.

In “I Can’t Make You Love Me,” I again heard the same differences in the bass and midrange. At the same volume, the McIntosh-B&W-SVS setup presented Bonnie Raitt’s voice with more presence, with her vocal inflections, rasp, and intonation more clearly conveyed. Conversely, the 8c’s sounded silky smooth, with no hint of sibilance, and made the McIntosh-B&W-SVS sound edgy and sibilant when voices were pushed hard in the mix. My wife participated in this comparison, and she chose the 8c’s, hands down. By comparison, she found the McIntosh-B&W-SVS difficult to listen to, almost irritating (we were listening at a fairly high volume).

She stayed on to hear the title track of Colin James’s National Steel (16/44.1 FLAC, Warner Music Canada) through both systems. As we focused on James’s voice, we heard a bit more presence with the 705 S2s, and cymbal crashes were slightly subdued with the 8c’s. While I marginally preferred the McIntosh-B&W-SVS rig for the extra sparkle and bite, and sharper leading edges on the sound of James’s acoustic guitar, she preferred the 8c’s for their smoother, less grating portrayal of his plucked notes — a matter of taste (and, perhaps, old age and mild hearing loss: mine, not hers).

Conclusion

The Dutch & Dutch 8c active speakers cost a lot, $12,500/pair, and their list of features is as long as my arm. Is their sound quality commensurate with the price?

Yes. In my smallish room, the 8cs delivered full-range bass — down to 20Hz — with a firmness, authority, and punch I’d never experienced before. Their midrange was accurate and smooth, if anything leaning slightly to the warm side; their top end was engaging, free of grain, and never over accentuated. They sounded realistic and transparent, and belying their somewhat pro-audio appearance, sonically they entirely “disappeared” in my room. Last but not least, they could play very loud without strain, compression, or edge — this small speaker could really rock.

Overall, the Dutch & Dutch 8c’s not only exceeded my expectations for how a pair of stand-mounted speakers could perform, in many ways they bettered the performance of my current setup of satellites and subwoofer in a room corrected with Dirac Live. If you can get over your preconceptions about what an audiophile system should look like, there’s no question: The Dutch & Dutch 8c is well worth $12,500/pair.